Panama Deployment

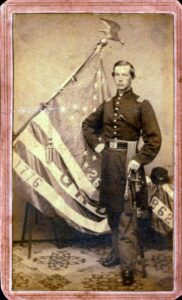

This Memorial Day, retired Air Force fighter pilot Jay Waitte honors the local Union Army soldiers who died to preserve that Union.

Next to Broadway Street in Norwich, Connecticut, there’s a small triangle of grass called Little Plains Park. It’s about one thousand feet north of my Waitte’s Insurance Agency office. There’s a 27-foot-tall obelisk in the park, partially obscured by trees. A dedication on the south face reads “To the memory of the 26th Regiment Conn. Volunteer Infantry.”

One day about 20 years ago, Bill Stanley, who we used to insure, approached me. At the time, Bill was a big mover and shaker in Norwich. Had been for many years.

Bill was also a well-known local historian. He said, “I want to do this project. Give me a grand and I’ll make a plaque for you.” So that's what he did.

The plaque reads, “This monument is to their memory.”

John Winsor of Sterling kept a diary. In it he wrote that on September 10, 1862, he had enlisted "…for nine months in the army of the United States of America (as part of an August callup of men by President Abraham Lincoln). I went into barracks on the 15th of the same month at Norwich to drill in the school of the soldier."

The Army assigned Private Winsor to Company G of the 26th Regiment, which was organized in Norwich in November. The men of the regiment were almost exclusively from New London and Windham Counties in southeastern Connecticut.

The regiment sailed down the Atlantic coast and arrived in New Orleans, Louisiana, on December 16th. It was attached to the 1st Brigade, 2nd Division, 19th Army Corps, Dept. of the Gulf.

For several months, the unit served peacefully at Camp Parapet, a former Confederate fort north of New Orleans.

In late May 1863, the 26th C.V.I. was transported by the ocean steamer Crescent upriver to participate in the capture of Port Hudson, one of the last two Confederate strongholds on the Mississippi River (the other one was at Vicksburg, Mississippi).

Private Winsor wrote in his diary, “We then fell in regimental line with overcoat, rubber blanket, two days rations, 100 rounds of ammunition-right faced and obeyed the order forward march.”

The fate of the 26th depended greatly on the capabilities of their Corps Commander, Major General Nathaniel P. Banks, a political appointee with little military skill. Banks wanted to attack the virtually impregnable Confederate fortifications at Port Hudson directly rather than lay siege. But he waited five days, giving the Confederate forces time to prepare. And when he did attack, it was haphazard and uncoordinated. Two assault groups attacked mid-morning; two other assault groups (including the Connecticut 26th) attacked that afternoon.

Winsor later wrote, “but ere (the soldiers) had measured half the distance between (them) and the place for action, (they were) met by a volley of musketry, solid shot and shell, that shook the strongest nerve and...the stoutest heart, and most daring, to seek a shelter, or hide his frame by lying 'supinely upon' his belly....

“…The 6th Mich. followed the storming party, and the 26th C. V. then, and behind came the 15th N. Y. V. who without thought or care killed not a few perhaps of our own men by careless firing.”

None of the Union attacks even made it to the Confederate parapets.

The plaque reads, “There were 557 men in the 26th Regiment, and on that single day, in the heat of the state of Louisiana, on the banks of the Mississippi, 52 were killed and 142 wounded.” A casualty rate of 35%.

The attack was a disaster, as was a second assault two weeks later. General Banks had to lay siege anyway, which ended on July 9th. Private Winsor later wrote, “Started at 4 A.M. to take possession of the surrendered fort. Entered at 10 A.M. whistling 'Yankee Doodle.'"

In all, some 5,000 Union soldiers were killed or wounded at Port Hudson. An additional 5,000 “fell prey” to disease or sunstroke. Confederate losses were 750 killed and wounded, with some 250 dying of disease.

Their nine-month recruitment completed, the 26th C.V.I. returned to Norwich on August 17, 1863, where they were mustered out. Local citizens sponsored a welcome home celebration at the very same Little Plains Park.

The Little Plans Park plaque reads, “There was no single event in the history of Eastern Connecticut that was more tragic than the Battle of Port Hudson.”

Thirty-six years later, the Connecticut General Assembly appropriated $1,000 to erect a memorial to the 26th Regiment and its sacrifice at Port Hudson. A $1,000 local match created a total budget equal to $63,000 in today’s money.

The obelisk was dedicated on August 19, 1902, on the regiment’s 39th annual reunion.

The next time you drive up Broadway and past Little Plains Park, remember the sacrifice of these young men more than 150 years ago.